Archive for the ‘Book Reviews’ Category

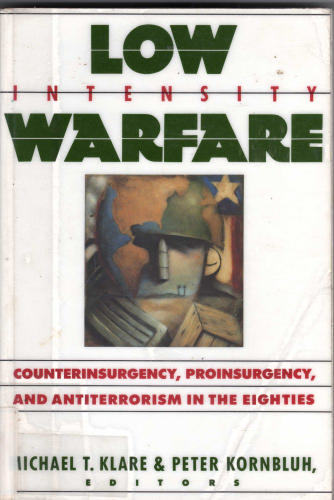

Book Review: Low Intensity Warfare

I would like to draw attention to this overlooked volume of essays on the new strategy of US intervention. Though the book was published in 1987, it might well have been written a few years ago. Indeed, many of its statements seem almost prophetic. From Vietnam to Guatemala to the Philippines, the authors of these essays follow the document trail and outline the birth of a new paradigm for US foreign policy. This book is invaluable for anyone seeking to place our actions of the 1980s into context. The aims of the Low Intensity Conflict doctrine, its publicly espoused justifications, and the deadly extent of its logic have only increased in importance over the 20 years since this book’s publication. Unfortunately, many of the lessons which precipitated the doctrine have been forgotten.

“Low Intensity Conflict” was a buzzword foreign policy specialists introduced in the late 1970s, though its practice and roots go back to the early 1960s. It entailed heavy support, both monetary and logistic, to insurgency groups within countries who do not act in a manner according to US interests. Leaders with whom we disagreed were often violently dispatched by guerrillas on the US dime. This was called “pro-insurgency”. On the flip side, we also funded vicious and brutal “counterinsurgency” campaigns, replete with mass arrests, interrogation by torture, forced labor, and the rest, to protect “our allies” from meaningful reform. In El Salvador, we gave a right-wing dictator carte blanche to destroy any and all organizations for social reform. He took it for a permission to murder, which it certainly was.

In every case the US consciously avoided using its own forces. The memory of Vietnam was still fresh in the public consciousness, so wherever possible our policymakers endeavored to induce others to commit atrocities on our behalf. Often this was done through monetary support and tacit encouragement. At times it was at our direct behest. Nine essays, contained within this book, outline the general concept of Low Intensity Conflict – from whence it originated, how it evolved, and how it has been put into practice.

Chapters 1-4 deal with the origins and development of the Low-Intensity Doctrine. Its roots go back to the Kennedy administration and Vietnam. A fresh new President for a hopeful new decade, Kennedy saw clearly the value of counterinsurgency. “What are we doing about guerrilla warfare?” he asked, literally on his first day in office. After realizing the answer was “not much”, he immediately enacted a series of National Security Action Memorandums (NSAMs) to bolster US capacity to fight counterinsurgency wars. NSAM-182 created a “Special Group” to manage all US counterinsurgency actions when it was drafted in 1962. Later that year, NSAM-177 gave Kennedy authority to bolster the South Vietnam police force. Slowly, South Vietnamese CI forces found themselves coming under US control. By 1966 NSAM-182’s “Special Group” had “internal defense plans” for thirty countries and ran the entire South Vietnamese CI forces.

But there were problems. In the first place, the delegate we assigned to fight the “commies”, an odious man named Ngo Diem, was beginning to disobey US orders. Oh, it was fine when he was using our resources to massacre his own citizens and institute a reign of terror – but by 1963 Diem caused the US more grief than pleasure. Much of this had to do with his increasingly lavish lifestyle, but it was mainly due to his ineffectiveness at combating the Viet Cong. There was also the consideration that the Low-Intensity doctrine (then called “counterinsurgency”) had not yet been tested in combat – and our policy makers were itching for an opportunity to do so.

For whatever reason, the CIA saw fit to assassinate their onetime partner Ngo Diem, which they did on November 11th, 1963. Major US involvement in Vietnam began only a few months later, but saw little more success at thwarting communism than Diem did. Although we manged to kill or maim far more than he could have dreamed.

After Vietnam, the foreign policy landscaped changed precipitously. The public had turned decisively against US military commitment, but it did not seem that they were against intervention per se – merely intervention that costs US lives. Our policy changed as well – not to one of non-interventionism, but one of non-committal. Throughout the ’80s, wherever possible, the US strove not to commit it’s own forces, and “let them [the citizens of the third world] do our fighting for us”. Chapters 5-9 of Low Intensity Warfare detail the fulfillment of such ambitions in El Salvador, Nicaragua, The Philippines, and Afghanistan, respectively.

El Salvador was our first major counterinsurgency effort since Vietnam, occuring less than a decade after the last US helicopter fled Saigon. In 1980, El Salvador saw itself undergoing rapid social change. The proportion of landless peasants had risen from 12 to 65 percent, the ranks of poverty constantly swelled, and revolutionary sentiment was in the air. The US could not allow populist reforms to occur in ‘their’ hemisphere – and so, President Carter sided with the military against the reformers. Thus began a horrific, decade-long civil war.

The US instituted death squad operations via the Salvadoran government, “which every morning littered tortured bodies in gutters and town squares.” (p. 115). “‘The Target”, as one U.S. diplomat described death squad operations in 1984, ‘is anybody with an idea in their head”, (p. 115). Between 1980 and 1987, the US provided more than $1 Billion in military aid to El Salvador. They also engaged in “Psychological Operations” (PsyOps), flooding the Salvadoran airwaves with pro-government propaganda. By 1987, over sixty-two thousand (62,000) Salvadorans had been killed by government forces.

In Nicaragua, we played the opposite game: pro-insurgency. There, the Nicaraguans had set up a social democratic government outside of US dominance. This was not something our policy planners could stomach, so they poured hundreds of millions of dollars into the so-called “Contras”, a right-wing guerrilla group battling the Sandista regime. We subverted elections, assassinated political figures, (again) funded death squads, and used our power to sow revolutionary chaos within Nicaragua. Notoriously, we funded both sides of the Iran-Iraq war, then used those ill-gotten proceeds to fund the Contras. By 1985, some 3600 civilians had died, 4000 wounded, and 5200 kidnapped at the hands of US-sponsored forces.

As a CIA handbook advised the Contras: “It is possible to neutralize carefully selected and planned targets, such as court judges, magistrates, police and state security officials, etc. For psychological purposes, it is necessary to gather together the population affected, so that they will be present, take part, and formulate accusations against the ‘oppressor.” (Italics mine) Of course the Contras took this as an incitement for terror, which it was. Rural hospitals, doctors’ offices, schools, agricultural cooperatives and so forth found themselves the principal victims of Contra attacks.

Amid this carnage, the US continued to espouse benign goals and the ultimate aim of “democracy” in Latin America. Never mind that when Nicaragua practiced such democracy, the elected government came under brutal, murderous attack by US-sponsored forces. Never mind that when a populist, democratic movement arises in the western hemisphere, the US colludes with oppressive governments to crush any hope of reform. In our world of circular logic, “Democratic” is defined as “performed or having to do with the US’. Thus, the US simply cannot act in an un-democratic fashion. It is a linguistic impossibility.

One can see clearly the effect Low Intensity Conflict doctrine has had on our current policy. When Donald Rumsfeld estimated the term of US involvement in Iraq to be “six days, six weeks – probably not six months”, he was espousing the basic LIC predictions. Wars in which the US supplies actual soldiers can only be short wars. Our policy planners this decade forgot the lesson of Vietnam – always have someone else do it for you. The impulse for intervention, of course, has not gone anywhere.